Does President Akufo Addo Deserve a Statue?

What the debate over the President's statue really represents.

During my days in PRESEC Legon, in the heady days of intermural high school debate, I loved to spend time in the library fishing pithy Latin quotes to bamboozle opponents with. One day I found this one:

“I would rather have men ask me why I have no statue than why I have one.” The statement is attributed to the Roman historian and esteemed statesman Marcus Porcius Cato, known as Cato the Elder or Cato the Wise.[1] Apparently, Marcus Porcius Cato used to get asked a great deal, why he had no statue in Rome, while many people of far less note than he had statues littered across the city. And that is what he would say to them in response. “I would rather have men ask me why I have no statue than why I have one.”

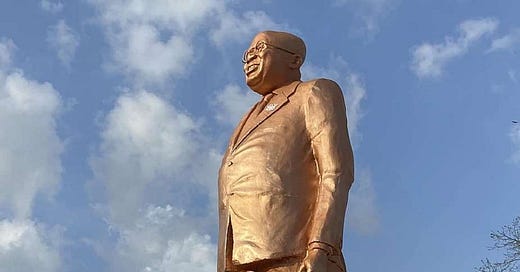

Recent events, you will not be surprised, have given me occasion to recall and reflect some more on this statement. A month to the 2024 general elections, the President of Ghana, Nana Addo Danquah Akufo Addo unveiled a statue of himself in Sekondi in Ghana’s Western Region. The statue caused no small stir, many feeling that the President did not deserve such an honour, on the basis of what is widely perceived as an uninspiring record of governance and leadership. It did not help matters that the statue President Akufo Addo unveiled stood in centre of a roundabout in a road whose construction was visibly incomplete. There were loud calls for the statue to be pulled down, and the main opposition party’s director of communications in the Western Region has made it his mission to have it relocated outside the region to Kyebi, the president’s hometown.

Since then, the president’s New Patriotic Party has been roundly defeated at the polls, losing by over 1.6million votes. The National Democratic Congress also swept parliament, winning 185 out of 276 seats, with the NPP securing 80.[2] Those results have been widely interpreted as a massive popular indictment of the NPP’s failure in managing the economy, fulfilling campaign promises and projects, tackling corruption, and putting an end to the illegal mining crisis facing the country, failures ultimately attributed to the president.

In the excitement of the elections and the aftermath, Ghanaians can be forgiven for forgetting momentarily about the statue brouhaha. After all, the nation is gripped by a tussle between the transition teams of the incoming and outgoing governments over pending budget approvals in parliament, and early action on an incoming anti-corruption initiative dubbed Operation Recover All Loot (ORAL).

If that were the case, we have been suddenly reminded after waking up to the news that the statue has been vandalised. Images and video have flooded social media. They show a statue with a hole in its left calf, and a missing commemorative plaque. While the statue has now been repaired, a burning question has been thrown into the debate halls of social media and Ghanaian broadcast media: should the president have a statue?

The public denouncement has come from many different angles. Two dominant ones are arguments from humility and merit. Some feel it would have been better to have had the statue unveiled by someone else, and better yet, built under another president’s tenure. The optics of having a statue of oneself erected in front of a major regional hospital are not good. Unsurprisingly, it made good campaign fodder for the NDC’s flagbearer, former President John Mahama, who admonished him to be humble and allow others to praise him. There are echoes of another kerfuffle in 2009, when then President John Agyekum Kufour creeated Ghana’s highest award and gave it to himself. Conveniently, the Grand Order of the Star and Eagles of Ghana is attainable only by people who have attained the position of President of Ghana. Back then, President Kufour was roundly upbraided for a lack of humility, and some even denounced the expense involved as wasteful and even corrupt.

Those who come from the merit angle insist that the president simply does not deserve such an honour for the failures mentioned above, and many more. Sympathisers however point to major infrastructure projects completed by his government as points in favour. Without doubt, a statue can be a powerful symbol. Far be it from me, however, to take a side in the matter. And, after the resounding defeat the NPP suffered in the election, I should say that this is certainly not meant to beat a man while he is down. I do not know how to determine whether the President deserves a statue.

Many statues have been controversial for many different reasons. In fact, I would dare anyone to produce one statue of any political figure in history that is wholly without controversy. Time and events also change the way a people feel about their leaders. Ghana has its own history here. Kwame Nkrumah may be lauded by most for his accomplishments and vision, but on the 24th of February, 1966, nine years after he led the country to independence from British colonial rule, his statue was toppled and beheaded. Mahatma Ghandi’s statue was removed from the University of Ghana following accusations of racism on his part. Many statues being pulled down in the UK because of their association with Britain’s part in the slave trade belong to figures who were cherished in their own day.

In the heat of contemporary politics, it may seem more clear cut to determine whether the president deserves it or not. But if history is the guide that it is, time will likely reveal to us how much more complicated the picture truly is when it is too close to you.

Rather than take sides, I’d want to suggest a different view on the matter, one that goes beyond the immediate discussion of whether or not the president should have a statue. Rather than provide a nice pithy pretext to a simplistic condemnation or defense, I believe Cato’s aphorism invites us to consider the deeper question of how a society decides what it values in democratic governance and leadership.

“I would rather have men ask me why I have no statue than why I have one.”

Who sets the standard for what is considered an acceptable level of development, vision-setting, and good governance? You see, buried in Cato’s declaration is a universe of values that I did not quite see in my days as a debater in high school. On what basis would Roman people have thought that Cato deserved a statue? On what basis would they have thought those many famous men who did have statues did not deserve them?

It is a question that has recently been asked with increasing frequency, even if in different ways. For example, the award-wining journalist Bernard Avle, in a now famous monologue in the studios of Citi 97.3 FM, has called Ghanaians to decide who “sets the question” that politicians claim and compete to answer when it comes to development. For too long, he laments, it has been left to politicians themselves to set the questions they are going to answer in the exams (these being elections). And this needs to change.

What Avle calls for, is nothing short of a paradigm shift. He says, “we need to define the question for the leaders.” Constant comparisons between the governance records of the two dominant parties, the NPP and the NDC, will mean little if they are allowed to set the standards themselves. Addressing comments by Freddie Blay, to the effect that the NPP’s economic record was better than that of the NDC’s, “he will say that because the question up until yesterday was, ‘six of one, half a dozen of the other; which is the lesser of two evils?’” For Avle, Blay and the majority of politicians are, conveniently for their political interests, setting too low a bar. The real question, he suggests, should be not which party has done better than the other on x, y, or z, but which can bring about a real transformation in the fortunes of the people.

By that metric, neither party deserves praise, and perhaps neither deserve monuments to their leaders. More so, victory in the elections should not be misread as a stamp of the people’s satisfaction. If left to the people, economic and social transformation felt on the personal level is what the standard would be. And Bernard Avle is clear: “to transform something means that when you look at the thing, you won’t even recognise the original.” Quite clearly, Ghana has not seen a true socio-economic transformation over the entire duration of the 4th Republic, which began in 1992. Avle is not the only one sounding the call. Youth all over Africa are calling for fundamental shifts in the way they are governed, and in the kind of vision they expect their leaders to articulate. The rallying call is for radical transformation rather than piecemeal gains.

But, let’s face it, it is an inconvenient standard if you are a politician. And politicians who shy away from lofty goals of transformation—not that they do so in their rhetoric!—will cite in their defense prevailing global economic challenges, unfair global economic structures, legacies of colonialism, neocolonialism, the exploitative greed of the West, and, among others, the attitudes of their own peoples to work, productivity, and care for the environment. But that is not good enough. While these are real factors, they are certainly no reason not to dream big.

Ghana, and Africa as a whole, is living through a period of dream impoverishment. Political leaders, by sinking into the mire of comparing themselves amongst themselves and against their own poor historical records, have been dragging down the thresholds of possibility for their people. Unfortunately, in Ghana, many are still trapped beneath that very low ceiling. It was not always like this. At independence, Ghana was a country not just of hope, but of ambition and optimism. Sadly, the vagaries of our politics seems to have convinced us that it was all just a foolish dream. We have lost our sense of dreaming big, of not only managing our own affairs, but of playing leading roles in addressing humanity’s common challenges.

This is a truly sad state of affairs, and it is perhaps the most fatal of all our flaws. Economic poverty stings hard. So does educational poverty. But a lack of collective ambition will ensure that the continent is left behind. The problem is particularly serious at a time in history when technology is fueling a new phase of imagination for the future of humanity. That imagination is marked above all else by visions of radical transformation in all spheres of life.

Back to the statue, then, it becomes clear that the key question is not whether President Akufo Addo deserves a statue. Like the hole in the leg of the statue, there is a hole in the logic of the question. Or rather, we need to vandalise the statue that the question represents. We need, forgive the cliché, to punch holes in its leg. For just as statues represent people, this question is a symbol of a collective focus on the wrong issues in our politics. It is a statue of a statue.

Don’t get me wrong, it is a valid question that provides a touchstone for the expression of differing political viewpoints. This is a healthy part of democratic discourse. But it does deflect from a more meaningful question: what should it take for a President to deserve one? What do today’s citizens consider to be a job well done by a government? A society must determine that for itself. And it is not that young people are not dreaming. They certainly are. Social media is making them more aware of how far behind Ghana is from the developed world. So at present, the dream is a cacophony of anxiety, frustration, and impatience. It needs fine-tuning into the pitch of an actual and preferably long-term plan of action, and that is where national dialogue becomes necessary.

This calls for a new era of collaborative, people-centred and people-sourced agenda setting. It calls for a new breed of Ghanaian and African politician that listens to the people. It calls for a consultative process in which the people can clearly communicate what kind of future they imagine for themselves. I hope the incoming government adopts a listening approach beyond mere platitude.

Cato’s statement reminds us, even if subliminally, that the people as a whole, and not just politicians, should set the agenda for development. If they fail to set the right questions, politicians will keep wrangling over meaningless self-comparisons, and we will keep answering wrong questions like whether or not Akufo Addo deserves a statue.

__

Agana-Nsiire Agana is a Ghanaian poet, social commentator, and academic. He researches technology and society through the lenses of philosophy and theology. He holds a PhD from the University of Edinburgh.

[1] Plutarch, The Parallel Lives, The Life of Cato the Elder, p. 359. https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Cato_Major*.html.

[2] At the time of writing, results from nine constituencies are pending declaration due to disruptions to the collation process, in some cases violent.

Question well framed! What will it take for a president to deserve a statue? I think the problem has been who will define the question? As a people we haven't settled on a defined collective aspiration. Any question that will require adjudicating on the stewardship of a politician will be a polarized one

The question of who sets the question for politicians to answer is the most important missing component of our democratic journey. As long as the country is run on the myopics of party manifestos rather than an encompassing non-partisan national agenda, we will continue to twist and turn in circles, cursing out politicians for providing us answers to questions we did not initially put to them ourselves.