The Omega Point of Imperialism

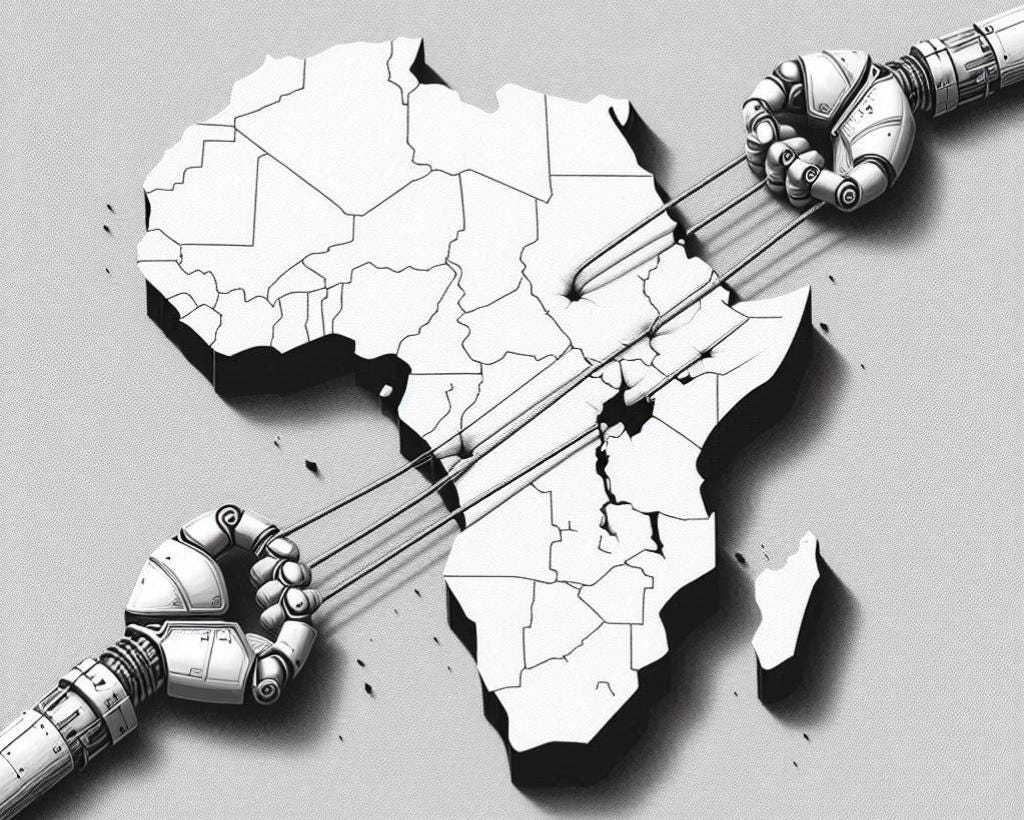

Artificial Intelligence, Big Tech, and the Coming Recolonisation of Africa

This article is the first in a series exploring the question of African prosperity in the coming postdigital age. It takes the current race for supremacy in AI amongst wealthy nations as a starting point for critiquing the aims and goals of tech-enabled global domination, and what it would mean for Africa. It lays the foundation for future instalments to explore how the AI Wars, as I dub them, revitalise old debates about unification and inspire a new conception of what that can look like. For your enjoyment and reflection.

With the Artificial Intelligence (AI) industry shaping up to be another economic arms race, there is near-universal consensus that the outcome will fundamentally shape the future of humanity. In this article, I argue that the race to dominate the Artificial Intelligence market poses an existential threat to Africa. Specifically, Africa risks a return to open recolonisation by a few powerful tech-state amalgams.

AI is fast becoming an integral part of global governance in all sectors of economy and society. The impact is felt in business, law, healthcare, governance, and all spheres of modern life. It also impinges on individual lives, shaping attitudes, conceptions, and worldviews. Even in the most defining and persistent elements of modern culture and thought, such as democracy and religion, digital media and technologies are already exerting a noticeable shaping impact. So much so that it is safe to say whoever controls AI will shape the future of humankind.

At the current rate, it is also safe to say it will not be Africa. This is such an obvious truth that it would be pointless to fish out a statistic to illustrate the meagreness of Africa’s contribution to the design and development of AI systems beyond the supply of raw materials for hardware devices. Suffice it to say that as things stand, up to 90% of the global AI market is controlled by the United States and China.

Africa does not register on the map at all. AI startups around Africa are doing important work in language preservation, healthcare, education, security, and more. But the totality of their footprint is minuscule on a global scale. What is more, many startups build applications that depend on existing models developed by and maintained in, Western countries.

But this is not another article about how Africa is being “left behind.” It is, rather, a more general warning that the AI wars can accelerate an already ongoing processes by which the continent is being displaced from the commonwealth of free nations. These processes I address under the broad term neo-colonialism. There are two connected reasons for this. The first is related to the nature of progress in computational science and AI development. The second concerns the relationship of this progress to the acquisition and exercise of power, a relationship whose nature has already been made clear in history.

Bloody Bedfellows

Colonialism, Capitalism, and Technology

Throughout history, if capital has provided the impetus for imperial expansion, technology has provided the means. This relationship is laid bare by a pattern of European expansion that began with intense competition between European kingdoms for access to natural resources from the farthest reachable edges of the known world. This was spurred by the advances in maritime and military capability, often through government-merchant amalgams. As the monarchs of Europe provided the license and sometimes the funding, merchant firms made available better and better technology and techniques for sailing the world and subjugating it.

A case in point was the often-tense relationship between the British government and the East India Company, which had grown so large that at one point it was allowed to mint its own currency and had its own flag and standing naval military fleet. Through the East India Company, England extended its dominance to colonies in Asia and Africa in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. The Company, as it is often called even today, controlled a large chunk of global trade, but also held great influence in other sectors of public life such as the provision of education as a tool of colonial subjugation. It was a union of politics and business that finds strong echoes in the convergence of big tech with political governance today.

I will return to this theme in due course. For now, lest we stray too far from the specificities of AI and digital technology, let us consider how technological progress today can give new life to this historical symbiosis.

Technological progress today is linked, of course, with the dazzling rapidity of computational progress. The nature of progress in computational processing speed follows a model known as Moore’s Law. It is “the observation that the number of transistors on computer chips doubles approximately every two years.”[1] That this law has held true for over half a century is a staggering accomplishment. But it is limited by the material constraint of hardware. Processing speeds are still increased, in the main, by increasing the number of transistors on a board. With recent improvements in AI, however, computational speed and efficiency is being significantly accelerated purely by algorithmic means. Computers are learning to “think” better, and the gains from doing so amount to real increases in computational power, so much so that for a decade already, they have surpassed the expectations set by Moore’s Law.

OpenAI’s ChatGPT, Google’s Gemini, and Microsoft’s Copilot are among the most well-known cases of such increases. But astronomical as the computational gains achieved by larger and larger models is, they appear to have been dwarfed by the achievements of China’s DeepSeek. Whereas American companies, which have held the lead in recent years, spend hundreds of billions of dollars on training their models, DeepSeek claims to have cut the cost down to about six million dollars. They claim to have done this purely on the back of algorithmic efficiency. If these gains are real, then the calculus of cost, access, and control, as well as the entire thinking about how to pursue AI advancement will shift fundamentally.

Of course, DeepSeek’s expenditure claims are being questioned. Be that as it may, nobody is questioning the plausibility of the claim, which in itself testifies to the seriousness that thought leaders give to the possibility for paradigm-defying innovations in the space. All this while Africa has not even yet entered the room.

The second and related reason is the relationship between that progress and the nature of power. In summary, it is not a healthy one. Consider, for example, that all this progress rides on the back of the exploitation of resource rich countries, many of which are in Africa. It is well documented that Western companies benefit from and in many cases are directly involved in the extraction of rare minerals used in the production of digital device hardware.

This has only intensified with the AI race. AI is now recognised as a force for recreating the structures and repeating the ills of colonialism. But the menace is, of course, not restricted to minerals. African persons are exploited as sources of data for training models. The phenomenon, known as data colonialism or digital colonialism, is a serious and growing one. According to whom one reads, data is the new tea, gold, or oil.

It has been defined as “the use of technology for the political, economic, and social domination of another territory.” This definition highlights the unchanged nature of power relations between poor African countries and rich ones bent on global domination through technology.

In many cases, these relations mirror old colonial arrangements. Infrastructure is created to ensure supply of resources and little else, and workers are treated under inhumane and dehumanising conditions. Further, Africans are also employed to screen and sanitise the most harmful of digital images and content for oversees big tech firms, often without the needed attention to their mental health and wellbeing, and certainly at nowhere near a justifiable level of remuneration.

This demonstrates clearly that the rise of digital colonialism occurs alongside what may be described as a digitally driven recolonisation of land and resources in Africa through overt capitalism and covert neoliberalism. Thus, while this is often discussed separately, I consider it a part of the same digital colonisation problem.

This time, the stakes are much, much higher. The stakes involve a kind of technological leapfrog by which the winning country can conceivably become capable of creating, protecting, and wielding an insurmountable degree of power over the losers. They are so high that contestants are incentivised to engage in open, brazen exploitation of weaker states to bolster their own bids for monopoly. This is what I fear will happen to Africa beneath the feet of the trampling elephants that are China, Russia, the EU, and the United States: overt recolonisation.

Up until now, open annexation of foreign territory has been seen as the preserve of undemocratic regimes like Russia and China. But with the United States threatening to colonise Canada and Greenland, and to take the Panama Canal by military force if necessary, we have entered a new paradigm of geopolitics that fundamentally challenges the idea of a postcolonial world. It is an era marked by a more brazen, ungloved approach to the assertion of power.

Does this open recolonisation mean African countries will once more be officially designated as colonies and lose their station as members of the United Nations? Perhaps not, and even then, only perhaps. Even if not, it does not mean that they will not have lost their sovereignty. As Kwame Nkrumah explained in The Last Stage of Imperialism, “The essence of neo-colonialism is that the State which is subject to it is, in theory, independent and has all the outward trappings of international sovereignty. In reality its economic system and thus its political policy is directed from outside.”[5] This is the threat posed by technological vulnerability today.

Technofeudalism and Recolonisation

Just like the East India Company of two centuries ago, today’s tech firms are becoming behemoths of not just global finance, but also cultural production and formation. The rise of digital cultures spurred by social media and AI does not happen in a political vacuum. Rather, it occurs at the instigation and under the design of powerful entities that arrange them according to logics of production and profit.

This is now a well-studied field in scholarship, and Shoshana Zuboff’s book The Age of Surveillance Capitalism paints a compelling picture of how digital technologies concentrate power in the hands of powerful political and economic entities.

In an age of surveillance capitalism, technology can be used to exert foreign control over weaker countries. It can also help those governments exert stricter controls on the lives of their citizens. This, of course, is already happening in various parts of the continent. However, the point here is a larger, more contextual one: the quest for AI dominance by powerful countries will leave Africa overexposed to the inevitable pressures imposed by those nations’ demand for resources.

African states will discover that the pretence of independence and sovereignty that these powers have allowed them to keep up will not hold. The lesson of history is that evil uncovers its mask when most desperate, and the risk of losing the AI battle is not one that the United States or China is willing to take.

Within that broader context, the AI wars are exposed as one part, perhaps the biggest part, of a larger struggle between old and new adversaries to redefine the global centre of power. This jostling amongst the United States, the European Union, Russia and China, is already playing out dramatically on the African continent. With all three vying for greater influence over Africa’s land and resources, the next colonial force will be determined to no small degree by who wins the technology race. It is more likely, then, that the next wave of overt colonisation will follow the new patterns of techno-feudalism that are emerging, in which one or a few countries or business entities rather than many, control access to resources all along Africa’s critical value chains.

Technofeudalism, a term coined by Greek economist and writer Yanis Varoufakis, refers to a new paradigm of global economics in which capitalism is not merely extended into something like surveillance capitalism. Rather, it is replaced by something like the feudalism of medieval Europe, in which feudal lords controlled land, labour, and, through this influence, politics. Varoufakis insists that just as the transition from feudalism to modern capitalism was not immediately noticed, technofeudalism displaces capitalism silently. In fact, it has already happened.

Varoufakis has his critics, and his analysis does risk a certain amount of oversimplification. However, there is no debate that the economic strategy of Big Tech hinges on the attainment of monopoly. That, as many economic theorists will point out, is nothing new, and is especially a feature of capitalism. The new Donald Trump administration is showing how influential an elite club of technology leaders can be in shaping global geopolitics, and the signs do not look positive for countries that come under the pall of the emerging tech oligarchy.

Former US president Joe Biden’s warning against the new “tech-industrial complex” should not be read as an America-only problem. The outgone president did not mince words: “an oligarchy is taking shape in America of extreme wealth, power, and influence that really threatens our entire democracy, our basic rights and freedom and a fair shot for everyone to get ahead.” I am reminded here of a Yoruba proverb: if a crocodile will eat its own young, what will it not do to the skin of a frog?

Now that Elon Musk has gained political importance in the new US administration, the white South African national’s recent Hitler salute, whether intended or otherwise, conjures no good images of what is in store for Africa.

In some parts of Africa, big tech companies have often fuelled conflict by trading in illegally sourced “blood minerals.” The Democratic Republic of Congo is suing Apple, which it accuses of turning a blind eye to the source of tin, tantalum and tungsten that are critical to the manufacture of its mobile devices. The irresponsible trade in tech-critical mineral resources has long been a problem. Today, it has become a symptom of the wider logic of brazen exploitation that structures the new economic order of the technology age.

My argument is that technology for the first time allows one player to attain a genuine and practically unassailable monopoly. It is now easy to imagine one company achieving such a level of algorithmic or computational breakthrough that it is able, not only to grow unchecked, but also to effectively restrict the growth of competitors; a snake that grows so big that it swallows up all others and lacks predators.

In the end, then, it does not matter how the emergent dispensation is characterised. What is clear is that it will be defined by a pernicious, possibly intractable exploitative element, and the nations that will suffer the most for it are those that hold the natural resources, data included, necessary to keep the beast fed.

The Omega Point: Imagined Futures, Real Pasts

The future sold to us in the wake of technological revolution is often a utopian vision in which technology helps humanity attain full health, wealth, beauty, and peaceful, prosperous global co-existence. When the marketers are not too absentminded, environmental health is also added to the mix: technology will help produce a future in which the worst of climate change and human-made environmental catastrophe is averted and the problems themselves overcome. These futures go by many names in popular and academic discourses: postdigitality, transhumanism, and critical posthumanism, being only a few.

Of all these discourses, transhumanism is the most popular. It is the belief that humans will evolve beyond their current biological potential as they merge with machines bodily and culturally. It draws on the philosophy of nineteenth-century French Catholic theologian Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, who postulated that all of evolutionary history was pulling humankind into a singular point of converged consciousness, the Omega Point. While de Chardin’s ideas are theological, secular proponents extend his ideas into the concept of the technological singularity, which is a similar state in which evolution reaches its apex in a singular consciousness that AI helps to bring about. Transhumanism motivates many different lines of research in AI and computer science.

An important dimension of the transhumanist vision is the attainment of artificial general intelligence. Often dismissed as science fiction by academics, AGI is the declared goal of many industry leaders, and of Donald Trump’s new Stargate Project. When industry leaders tie the pursuit of AGI to the aspirations of a single power bent on dominating the technological landscape, the warning bells should not be able to ring louder.

This is because at the core of transhumanism is a vision of human evolution easily weaponised by, if not itself rooted in, racist interpretations that place whiteness at the apex of the evolutionary process, and that aim to secure its place within the new transhumanist utopia/dystopia. The echoes with Nazi propaganda about the evolution of the races and the superiority of the white race above all others are unmissable, even if there is some debate as to how correct it is to attribute that propaganda to Darwinian evolution properly understood.

Whatever the case, the rise of a tech-oligarchy with a prominent figure unafraid to publicly brandish what appears to be a Hitler salute, should trouble sleep. Nor am I an expert on the exact nature of Elon Musk’s exposure to the ideologies of white superiority that flourished in apartheid South Africa where he grew up. But again, it would be at best irresponsible to turn a blind eye. I do not mean to be alarmist, only to point out that connections exist that demand sober, critical reflection.

Another dimension of the transhumanist vision is a convergence between the human mind and that of the machine. This convergence is touted as ushering in a new phase of humanity in which our potential for knowledge and understanding is unleashed, and along with it, our ability to have dominion over the universe, and subdue it. But the question must be asked whose mind is to be fused? Also, on whose mind is the machine’s mind modelled? In whose image is AI being built?

All three discourses, however, are largely shaped by Western perspectives. Without serious consideration of non-Western perspectives, we cannot expect any realisations of any of these imagined futures to cater to humanity’s needs in any truly holistic way. We can see this in countless examples of real pasts. When the American colonies of Britain were vying for independence, they adopted the flag of the East India Company. The founders were sympathetic to the rebellious element represented by the Company. On a deeper level, I can imagine they would also have sympathised with the Company’s ideology of integrated commerce and politics.

While we cannot fully ascribe the development of the United States’ free capital economic ideology, along with its entrepreneurial individualism, to the East India Company, I am convinced that deep connective tissue lies between them. History lays bare what this outlook meant for the indigenous peoples of the American continent, for millions of Africans who were brought there and enslaved. To this same capitalist spirit can be laid a large portion of the blame for the European colonisation of Africa in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

The spirit of capitalism has been (mind you, I do not say it is because I consider that a philosophically more complex claim), the spirit of conquest and subjugation for the purposes of resource exploitation. Big Tech grows out of the womb of that history. The link between the East India Company and today’s tech companies is already a theme of growing reflection, with some reflecting on the parallels between their operations, others on more direct philosophical and ideological connections in the area of culture and knowledge production, and others still exploring the significance of the parallel for today’s excluded peoples.

Big Tech may not be the ghost of The East India Company and other mercantile companies like it (e.g., the Royal Africa Company, the Dutch West India Company, etc.), but it is a descendant, however obscure the lineage may have become over time. This is not to say that no good thing can come out of it for formerly colonised peoples. But for that to happen, our dealings Big Tech must be as open-eyed as Kwame Nkrumah was when, inaugurating a new shopping centre of the Dutch United Africa Company in Accra, he said his government “does prefer the devil it knows to the devil it does not know.” Up to now, sadly, Africa’s dealings with Big Tech have been anything but open-eyed.[1]

Scholars of Africa have rightly observed, for instance, that the continent’s technology policies uncritically reflect the entry of neocolonial logics into African governance. After studying the African Union’s science and technology policy, Lloyd Delroy McCarthy says the following:

Using Nkrumah’s lens to securitize the science and technology plan and strategy reveals an uncritical, pro-West, neoliberal, a-historical, conception with the tendency to perpetuate what Nkrumah called neocolonial relations.[2]

His conclusion is based on the observation that

Although mobile communication technology is experiencing the rapid growth across the continent no evidence was found that the African Union is developing or contemplating the preparation of a unified policy or standard for spectrums management and the implications of relinquishing control of the continent’s telecommunications infrastructure to a handful of foreign investors.[3]

Likewise, Arthur Gwagwa warns in a recent essay for Chattamhouse, that “If dominated by major powers, AI development risks creating a new form of digital colonialism, particularly in Africa and other parts of the Global South.”[4] As already stated, much of the exploitation we see of African mineral resources and human capital and data already tracks old colonial lines. My argument is not, then, as farfetched as it might first appear.

Further, as many historians and political theorists have noted, colonialism is apt to take new forms rather than give up easily. Nor is the technological phase of that reconciliation hidden from view, as we have seen above.

What to Do?

Not all are blind to the threat, of course, and especially among scholars, there is a growing conversation about how to ensure that Africa’s embrace of technology does not end up hurting it yet again. But in many instances sadly, the discourse amounts to an almost delusional appeal to the morality of a modern human rights and humanitarianism based code underwritten by Western powers themselves. In academic circles, this manifests as an appeal to the ethics of AI safety and decolonisation. In the business and political spheres, as well as in the sphere of civic society and non-governmental organisation, it is heard in repeated calls for more investment into digital technology research, coding, STEM, and a host of other platitudes.

Those analyses that focus on AI likewise appeal to regulators and developers to enshrine ethical codes that will protect against colonial tendencies. In theory, this so-called decolonisation of AI could play a part, and very good work in this area informs the development of African policy approaches like the Continental Artificial Intelligence Strategy, which aims to harmonise AI policy across all fifty-five member states. Others advocate the development of African AI that embodies African values and considers the impacts of the tech industry on African people.

A lot of my own work as a scholar of digital culture is based on that hope. But I am also open-eyed to the signal lesson of history that it will not be anywhere near enough. The goodwill of the oppressor has never been the subaltern’s salvation. What is required is far more basic, and far closer to home, than that.

To buffet the current that is attempting to sweep the continent aside, Africans need to find a way to face the problem as a continent rather than as individual states. This is not a reprisal of a post-independence campaign for political unification. But success will depend on a form and degree of collaboration not seen before on the continent. More than that, it will take a level of self-knowledge African peoples have yet to experience. And if they do this, they will stave off not just the threat of technological subservience, but a whole horde of other ills. After all, my argument in this article is not only that Africa risks a technological subservience in the face of the AI race, which it does, but that it risks a return to de facto if not de jure colonisation in a holistic sense.

The tools of resistance, then, as I will argue in the next instalment of this series, can be effective not only against the threat of AI, but also against a panoply of conditions involved in the perpetuation of neocolonialism. After all, Nkrumah was right about one thing: “our enemies are many and they stand ready to pounce upon us, and exploit our every weakness.”[6]

Conclusion

Okay, so this has been very doom-and-gloom-y. But many of the associations I have claimed in this article, whether between colonialism and capitalism or between transhumanism and racism, are mentioned not to be sensationalist or alarmist for the mere sake of it, but to awaken serious thinking on what it means for Africa, and indeed the rest of the world, to allow the AI race to carry on on current terms.

AI presents the means by which new tech-state amalgams can achieve a level of colonisation far more pernicious than anything the African fathers could envision or prepare us against: the omega point of imperialism. Coupled with this, we are witnessing the rise of a tech-industrial complex that is forging deeper and deeper links with powerful state actors openly using the language of conquest.

These are bedfellows in a mix of capital and oppression that has been brewed many times over the course of history. Thankfully, history should also provide ample resources for reflecting on effective ways to counter these new threats. In the next article, I will explore how the recent history of a debate on African unity bears on the threats discussed here. In the meantime, they should indeed cause concern, and especially in once-colonised lands. They should even cause alarm: does history not warrant it?

References

[1] Bianca Murillo, “‘The Devil We Know’: Gold Coast Consumers, Local Employees, and the United Africa Company, 1940—1960,” Enterprise & Society 12, no. 2 (2011): 317–55. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23701393.

[2] Max Roser, Hannah Ritchie and Edouard Mathieu, “What is Moore's Law?,” March 28, 2023. Retrieved February 1, 2025, https://ourworldindata.org/moores-law.

[3] Lloyd Delroy McCarthy, “Africa’s Science and Technology Strategy,” Socrates 3, no. 1 (March 2015): 130.

[4] McCarthy, 130.

[5] Arthur Gwagwa, “Resisting colonialism – why AI systems must embed the values of the historically oppressed,” Retrieved February 1, 2025 Chattamhouse, https://www.chathamhouse.org/2024/06/artificial-intelligence-and-challenge-global-governance/06-resisting-colonialism-why-ai.

[6] Kwame Nkrumah, Neo-Colonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism (London: y Thomas Nelson & Sons, 1965), 4. https://www.marxists.org/ebooks/nkrumah/nkrumah-neocolonialism.pdf.

[7] Kwame Nkrumah, “Steps To Freedom.” Edited by Solomon Appiah, retrieved February 1, 2025, https://www.sunesislearninginitiative.com/insights/217/steps-to-freedom-by-dr-kwame-nkrumah.